Introduction

Standing Together was a virtual vigil that was held by St. Timothy’s Presbyterian Church in solidarity with Black people who face disproportionate racism in the United States and Canada. The vigil took place on Saturday June 6th, 2020 with roughly 100 people in attendance. This event featured two guest speakers: Rev. Dr. Esther Acolatse (Associate Professor of Pastoral Theology and Intercultural Studies at Knox College), and Rev. Paulette M. Brown (Minister at St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Humber Heights, Toronto).

Where is the Love? – The Black Eyed Peas

The video below was re-arranged to depict the current protests and calls for justice, and to capture the feelings and emotions of the recent Black Lives Matter movement.

Why We Are Here

On behalf of St. Timothy Presbyterian Church, I would like to welcome all of you to this online vigil. I am Simon Park, an associate minister of this church, along with the senior Minister, Rev. In Kee Kim and our other associate minister, Rev. Soo Jin Chung.

This vigil began as a humble event for our church members to come together and stand in solidarity with our black brothers and sisters who bear the weight of anti-black racism. It quickly spread, however, to members of other churches and those beyond. It indicates the deep desire to stand in solidarity.

The cruel death of George Floyd has set off an eruption of emotional response across the United States and the world. We are here partly to process and reflect on that shock.

The forces that have brought us here together, however, are quite unique. We are living through a pandemic unseen in our lifetimes. One thing this pandemic has made clear is the importance of life. It has made us look at life differently, and cherish life as the precious treasure that it is.

But recent events: Ahmaud Arbery, Christian Cooper, Breanna Taylor, Regis Korchinski-Paquet, and most notably the death of George Floyd, have brought to the forefront of people’s consciousness the reality and depth of anti-black racism. It has brought to life the sinister reality of racism that would degrade the dignity of life. This consciousness has unleashed a raging hunger for justice.

We see that life cannot flourish without justice. A flourishing life and justice go hand in hand. When justice is choked off, life is choked off.

Last Sunday was Pentecost: it marks the beginning of the church, when the Spirit breathed life into it. But we can’t breathe.

When there is injustice, the Spirit cannot breathe in us. The Spirit gets choked off. Life gets choked off.

Why are we here?

To listen. To stand in solidarity with the black community. To confess, repent and seek a new way forward.

Let us begin this vigil with utmost humility, asking our God to lead us toward justice and life.

Reflection by Rev. Dr. Esther Acolatse

Good evening!

Today I say, brothers and sisters, to say that I have been angry is an understatement. I have quarrelled with God, and talked at length, and walked my house, and raised my fist to the heavens, and demanded things. But, I am also a theologian, and a psychologist, and I think that in this time, anger is our best friend. Anger is our best friend. So, what does it mean to talk about our anger and God’s righteousness, and ask of God justice, when we know that scripture says that our anger does not work the righteousness of God? And yet, I’m beginning by saying how angry I am, and how for me, anger is my best friend. So, why are we here? And why have you gathered to, as it were, as the song we began with said, stand in solidarity with people like me?

I have a black son. I cannot tell you what it means to live in a racialized world and have a black son. You carry your heart in your mouth everyday, your body does not know what rest is, until they have returned home. Many years ago, when Ferguson happened, Duke asked me to write something, and I ranted, and you might find it online, “To Mothers of Black Boys, and All Who Love Them” is what it’s called. But, then I look at my own story, a simple girl from Ghana in Africa, whose first self consciousness was not of difference. I didn’t grow up thinking someone was different from me, or others based on skin colour. I came into the United States, or North America as we want to say it, when I was 34, and yet, today, what psychologists call ‘allostatic load’, is my lot. Your body doesn’t know rest, the wear and tear on the body which accumulates as an individual is exposed to repeated chronic stress is what we call ‘allostatic load’. What some of us are feeling, in this period of pandemic, a few months, is what an African American lives with every day.

I ask myself what it means to be human, and to live with other people whose humanity is dependent on their interrelation with you. If you live in helplessness, that forms you for hopelessness everyday. What it makes of you and who you really would have been, but for this racialized living. And what it means for the other who interacts with you, who knows themselves only in association with you. Who would they be if they accorded you full humanity? So, who are we?

I started by saying that in this season, anger is our best friend. There are abiding characteristics of anger that are righteous and lean into who God is, if it is about life. Life at the very core of God’s being, who made us in God’s image. If my anger is because someone is messing with life, then it leans into who God is, and what God cares most about. So in this case, this anger is right. But, we also know that it is right when it is shared, like you gathered on this platform to share in our anger. If you can feel even a quarter of what I feel as a black person, then this is not wrong anger. In that sense, anger is what helps us through tribulation. When scripture talks about tribulation, which we try to bandy around, you know, we all do trials and tribulation, it is actually when the history of your life is trying to make mincemeat of you. The grinding constant pressure is what we call tribulation. And anger, like hope, becomes your springboard for pushing back and saying no to this thing that comes from the pit of hell.

So, why are we here? And, why do Christian people want to stand in solidarity with people who may not be related to them? I think the answer lies in our scriptures. If we believe in creation rather than evolution, then we know that all of us are made of God. To live in a racialized world, and not mind, is worse than blasphemy because it says that even if God made us, God made some people better than others. That is already a serious theological problem. But, the worst part of it is that it says that if God made all of us in God’s image, then God has good parts and bad parts: good parts that made certain kinds of people, and bad parts that made certain kinds of people. Sit with that for a minute.

Why are we here? And why do you want to stand with me? I can tell you horror stories of being followed by cops, of walking through Harvard with a few friends from Boston, and when I say I go to Harvard, somebody would say Howard. I assumed, “Oh, it is my accent.” Four years later, I get to D.C, and realize that there is a school called Howard, which is for black people.

That which says that there is certain space allotted, for a certain kind of people, and that certain people that we have put in a little corner somewhere should stay where they are, and if they move even a millimetre towards where we think they should not be then we will react. That is what is showing up in the killing of Floyd and, the worst for me, Amy Cooper, letting you know that when I call the cops, they know what to do.

I have to say this so that our being together is also a real being together. If I am walking with an asian, just by virtue of skin colour and hair they trump me (no pun intended). It means that this kind of racialized existence that has been carved erroneously by some white people has been sold in other places and they bought it. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve walked into a Korean Beauty Store in the US and gotten the eye and the following, just in case I might steal something. And then even in my own country, people who are lighter than me are considered prettier.

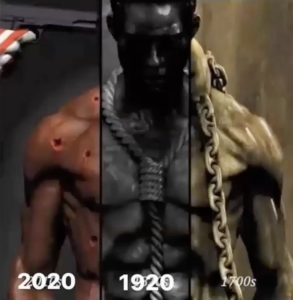

This is why we are here, I hope. To share this anger, to help fight justice. Not for Floyd, not for me, not for any black person that you know, but for the truth of the gospel. And I know that the Church has work to do and it is more than able to do it. Because we have someone who came in a body that is closer to mine than a white person’s body. Who knows how to mediate anger so that it does not turn into hatred. And if we lace our anger with God’s righteous indignation against racism, against dehumanization in any form of any people – even though the Black African female is the lowest of the low on that totem pole of who is who – then we can get work done. And I hope this vigil is only a beginning. I have sent a picture to Simon to share on the screen to give us a visual of why we are here and why the anger that is escalating everywhere today.

1700 to now. This is why we are here. The 1700s, 1920, 2020. Until we do something this is us. Unless we are tacitly saying that this was not made in the image of God. May I say again, that is my son. Thank you.

Prayer of Confession, Repentance and for Justice

Let us pray.

Dear God,

We as human beings are your delight. We were entrusted to take care of this earth and each other. But we have failed.

Here in Canada, those in attendance at this vigil, for the most part, have benefitted from the systems and institutions that constitute Canada. We have been grateful for the benefit that these systems have conferred onto us. But we have turned a blind eye toward those to whom this system has not been good. Those to whom our institutions have systematically treated with less dignity, less fairness and even cruelty. We are reflecting specifically right now on our black brothers and sisters.

The majority of us have bought into the notion of Canada as a nice, fair and generous country for all. When told by voices on the margins that not all this enjoyed fairness and generosity, we met those voices with shrugs, disbelief and even denial. The shield of the myth of Canada’s niceness has been difficult to penetrate.

We may have heard of, and even gone so far as to acknowledge, that there is anti-black racism in this country, but if we are honest with ourselves, we never paid much heed to it. We prioritized other issues as more important. At its core, we did not want to look at race, and in particular anti-black racism, as a problem for us here in Canada.

We have been like the priest or levite, who may have seen the injured Samaritan, but passed by on the other side. We have passed by on the other side of our black brothers and sisters who regularly have corrosive and insidious racism inflicted upon them. We have passed by as we tucked them away into neighbourhoods that we never venture into. Forgotten and out of sight. Forgive us for our blindness, denial, ignorance and indifference. Help us to seek a better way. Help us to be a neighbour.

For our church of St. Timothy, born in the Korean immigrant community, we too have confessions to make. In our colonization, being victims of global geopolitics in the Korean War, to the hard years of immigration, our psyches have been damaged, and we have been a fearful people. We should have been the first ones to understand the plight of our black brothers and sisters, and the first to join in solidarity with them. But in our desire to escape from our powerlessness, in the grip of fear, we sought acceptance and embrace within the economic and social power structure to find our sense of security and safety. We exerted all of our energies to be accepted within that power structure. In doing so, we pledged all of our allegiance there. To the very systems that exclude and inflict damage on our black brothers and sisters.

Yes Lord, we gave allegiance to that system. We became complicit with it and internalized the views and opinions of that system. We conferred legitimacy only to the voices of that system. In our fear and insecurity, we turned to power, and turned away from the voices on the margins. We confess these sins as we allowed our fear to drive our actions.

We all pray for repentance. To turn around and face those on the margins. To listen to their voices. To see them. To know them.

It is long, hard and difficult work. Help us oh Lord to examine our hearts, attitudes and biases honestly and critically. Give us the courage to face our prejudices and our indifferent or hostile hearts when it comes to our black brothers and sisters. We pray that our current sentiment not just be an emotional wave we are riding, but a commitment rooted in your calling for us to be stewards of human dignity for all.

We pray for justice. May justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream. Justice that is love personified in our society. For only with justice can life truly flourish.

May Your Spirit move within and through us to bring about healing and change. May you heal the hearts of our brothers and sisters rent apart by death and indignity. Beginning with our hearts, then into our thoughts and actions, may we then be humble partners and stewards of your justice and love.

In Jesus’ name we pray.

Amen

Guest Speakers

Rev. Dr. Esther E. Acolatse (Ph. D Princeton Seminary), is an Associate Professor of Pastoral Theology and Intercultural Studies at Knox College, Toronto, having joined the faculty in 2017. Originally from Ghana, where she was born and raised, Esther is a life-long Presbyterian, and has previously been Assistant Professor of the Practice of Pastoral Theology and World Christianity at Duke Divinity School (Durham, N.C.) since 2010. Recently, she became an ordained clergy within the Presbyterian Church (USA). Dr. Acolatse graduated with a bachelor’s degree (with honours) from the University of Ghana with a religion and psychology major, followed by a Master of Theological Studies degree from Harvard University. She then earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree from Princeton Theological Seminary. Esther explores the intersection of psychology and Christian thought, with interests in the gendered body, methodological issues in the practice of theology of the Christian life, and the relevance of these themes in the global expression of Christianity.

Rev. Paulette M. Brown (B.A., M.Div.), is currently serving at St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Humber Heights, Toronto. She was born and raised in Jamaica before emigrating to Canada in 1983. She graduated from Knox College in 1991 and began her life of ministry. She served University Church for 8 years where she developed the Created For Life youth ministry as a response to the violent and premature deaths of black youth in her community (She received the YWCA Women of Distinction Award for her work on that mission). From 2008 to 2014 she served the Presbytery of East Toronto and developed a mission for newcomer families at Gateway Community Church. Rev. Paulette Brown has also served internationally as a keynote speaker for the Presbyterian Women’s Gathering, gender consultant for the World Communion of Reformed Churches and a member of the writing team for the Council for World Mission.

Leave a Reply